Astronauts for Space Exploration

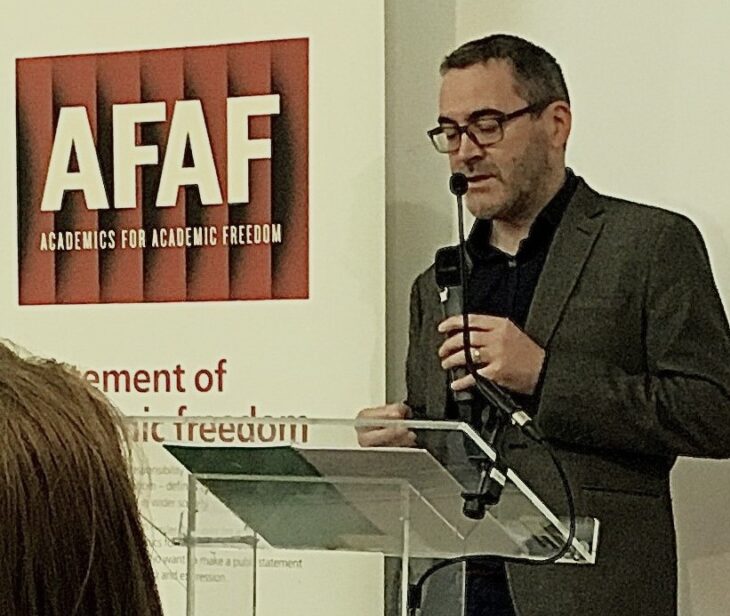

Tim Crowley gave this entertaining and insightful talk at the AFAF Annual Conference 2024

‘Academics for Academic Freedom’: I want to begin by just reflecting on this phrase. What does is it mean? What does it mean to be an academic for, or in favour of, academic freedom? Why, indeed, do we need an organisation, a campaign group, consisting of academics, to fight for academic freedom?

It might actually seem almost tautologous—imagine: you introduce yourself as an academic, and you get asked— ‘Oh, so is academic freedom important to you?’

Such a question should be met with an incredulous stare, as if the term ‘academic’ had not been properly understood; as if, on saying you’re a bachelor, you are immediately asked— ‘So are you married or not?’

Or better if one were to ask an astronaut— ‘Is space exploration important to you?’

Or worse: ‘Do you believe in space travel?’

You wouldn’t expect an astronaut to answer— ‘Oh, I don’t really think about space exploration all that much’; and certainly not— ‘I don’t know much about space travel’.

That would be very strange. I imagine one doesn’t find an organisation, a campaign group, consisting of astronauts, called ‘astronauts for space travel’; would be rather like ‘astronauts for doing what astronauts are meant to do’. As my fellow Corkman Roy Keane might put it, ‘That’s yer job! You’re an astronaut, that’s what you’re supposed to do!’

But… we do have this organisation called ‘AFAF’, and I think we need it—even though, I would suggest, one cannot do one’s job as an academic without academic freedom.

So why do we need it? Why are we here today?

At least part of the reason is that academics, a significant portion of academics, would indeed answer the question, ‘Is academic freedom important to you?’ by saying, ‘I don’t really think about it all that much’—or indeed, by saying ‘I don’t know much about academic freedom’.

Take the Irish case—which is what I’ve been invited over to talk about. In a recent survey of academics based in Ireland, by Terence Karran, 30%, almost a third, disagreed with the statement ‘I have an adequate working knowledge of academic freedom’.

This is higher than the EU average; but personally I think the figure is far too low. 70% have an adequate knowledge of academic freedom? Really? 70%?

If the figure is accurate, then the academics who participate in college and university committees, those that produce policies and codes of conduct, must be drawn almost exclusively from that 30%! I say this because of the frequency with which policies are drafted with no apparent account taken of academic freedom—or indeed that are in direct conflict with academic freedom.

For instance, in my university’s Statement of Academic Freedom—my university being UCD, University College Dublin, the biggest university in Ireland—there is a clearly worded warning to policy drafters: ‘No policy should be adopted that would deliberately or inadvertently diminish or inhibit freedom of expression among members of the university—staff or students’.

No policy? Oh well, I can tell you that this stipulation is routinely ignored. Just to take the issue of students’ freedom of expression; UCD’s policies directed towards students—such as its Code of Conduct—have been exposed as restricting free speech to a very high degree. In 2022 I invited the FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, to assess the health of free speech at UCD, and, to my surprise and delight, they agreed to do so—the first time the FIRE had ever assessed a non-US university. The results were damning: FIRE found that UCD, if judged as a public US university, would rank among the ten worst universities in America for free expression.

No policy, eh?

Now this report was published in July 2022; it was the subject of an article in the Irish Times—Ireland’s ‘paper of record’ on the day of its publication; and it was raised in Parliamentary Questions a few days later; but it was totally ignored by the university.

Indeed, UCD blithely continued to push policies restrictive of freedom of expression. Just two months after the FIRE report, UCD introduced a ‘training in Dignity and Respect’ course, to be taken by staff as well as students—the training culminated in a ‘pledge of commitment’ to the Dignity and Respect policy—a policy that was among the many highlighted in the FIRE report as a threat to free expression!

Now, I should say, at this point, that I am singling out UCD here, but with good reason—it is my university; and, as mentioned earlier, it is the biggest university in Ireland. But it is not an outlier in terms of free speech. In fact, my impression is that things are as bad, if not worse, in other universities and Higher Education Institutes in Ireland.

In any case, that’s the free speech situation. What of academic freedom, strictly speaking? A healthy culture of free speech would not, of course, guarantee respect for academic freedom; but it would make it more likely. So what is academic freedom like when there is not a healthy culture of free speech?

The thing about academic freedom is that we have excellent legal protection—or de jure protection—in Ireland. The Universities Act, 1997 is an impressive document; Section 14, on academic freedom is really outstanding. It identifies as a duty, a statutory duty of the university, not merely to protect or preserve the traditional principles of academic freedom, but to promote academic freedom. Do our universities respect this duty? Do they? Do they hell.

And here we come to the second major issue for academic freedom in Ireland (after the first issue, which was ignorance).

The de jure protection is sound; the de facto protection is lacking. There is no designated route of appeal, no office to which one might turn if—or when—one believes that academic freedom is being threatened—or being explicitly breached. In the survey mentioned earlier, a huge 92% of academics agreed with the proposition, ‘It is important that complaints of academic freedom violations can be directed to a departmental or faculty grievance body’. There is, then, significant desire for holding the university—or externa bodies—accountable for breaches of academic freedom.

At the moment one’s only hope is that a significant number of one’s fellow academics notice a threat and speak out together. This has actually happened, twice in fact, in the last four years at UCD; most recently, indeed, against the very Dignity and Respect pledge I mentioned earlier. My union, IFUT (Irish Federation of University Teachers), together with other academics, raised a complaint about the very idea of academics being asked to pledge commitments; and in the face of this opposition, the pledge was quickly—and quietly dropped.

More notably, in March 2020 a significant number of academics criticised the university’s attempt to alter the aforementioned Statement of Academic Freedom. An Addendum had been proposed that would have had the effect of diluting the statement. Why? In order to facilitate UCD’s expansion abroad—obviously with a view to financial gain. As the Addendum put it, in some countries the ‘European understanding’ of academic freedom might not be ‘appropriate’. Guess which country in particular… The backlash from academics led to the abandonment of this cynical assault on academic freedom.

So that’s good, right? Yes… and no. The fact is one cannot rely on one’s fellow academics to always take up the baton to fight for academic freedom. For despite these two examples of academics up in arms over the notion of being coerced to take a pledge, or over the idea of academic freedom being sacrificed to secure funding, many of these same academics have been quiet over the most evident and direct threat to academic freedom in Ireland. I am referring to Advance HE’s Athena SWAN charter, which dominates the Irish Higher Education System. Here, again, we have a pledge of commitment—a number of commitments. The very first line of the application letter template explicitly demands a ‘pledge of commitment to the principles of the charter’. These principles are politically and philosophically contentious, none more so than the demand to pledge commitment to gender ideology—to quote, a commitment to ‘fostering… collective understanding that individuals have the right to determine and affirm their gender’. Moreover, to be eligible for government funding, institutions must show they are engaging with Athena SWAN.

So here, just like the 2020 attempt to curb academic freedom for lucrative financial streams, we have another blatant curb on academic freedom and freedom of expression, tied to a threat regarding funding—in other words, there is a financial incentive to limit academics’ statutory rights.

Athena SWAN, as its own proponents describe it, is a ‘sanction led initiative’; it boasts in its literature that tying eligibility for funding to holding an Athena SWAN award is, quote, ‘an effective stick’ to ensure—to coerce–compliance.

Why has there been no pushback from academics—as we saw with the pledge and the Addendum to the Statement? Indeed, with regard to the latter, one of the most vociferous complaints came from someone who, at the time, was in charge of her own School’s Athena SWAN application—a remarkable instance of cognitive dissonance. How do we explain it?

Like this—and this leads us to the final challenge facing AFAF—or specifically, Irish AFAF, Dublin Universities Academics for Academic Freedom (after the challenge of ignorance, and the lack of redress procedures for violations). There is no outcry against Athena SWAN because so many academics believe in the Athena SWAN principles. And as I have discovered, urging colleagues—even in my own School of Philosophy—to see Athena SWAN as a threat to academic freedom is very difficult indeed. To counter Athena SWAN, a different move is necessary—one must go beyond one’s colleagues, beyond one’s own university; and take the battle directly to the Higher Education Authority.

So with regard to the three challenges identified here: with regard to the first, raising awareness (a corrupted phrase, forgive me) can work. There is indeed ignorance, but also a desire to know more. But as for the second and third challenges… well, the nature of the issue here is such that it tempting to parody the title of one of those anti-racist books— ‘Why I am no longer talking to academics about academic freedom’. What I mean is that the ad hoc challenges that some academics have made towards threats to academic freedom, even though they may meet with success, are simply too ad hoc; they are hostage to the whims of a demographic that is almost completely biased towards left wing social and political agendas. What is needed is some sort of independent formal office of redress, established to investigate all and any breaches of the traditional principles of academic freedom, and armed with the power to force universities to remedy such breaches and thus comply with the Universities Act. The Athena SWAN Ireland ideologues have perhaps shown us the way forward, in their capture of Ireland’s research funding bodies. Why not link eligibility for funding to the execution of the university’s statutory duty to protect and promote academic freedom? In other words, a campaign for legislation to enforce compliance with the law—in the form of the Universities Act—may be the best way forward. Who would oppose such a piece of legislation, save those who wish to expose themselves as enemies of freedom—and the law?

Dr Tim Crowley is associate professor/lecturer in philosophy at University College Dublin. He is the convenor of the Dublin Universities AFAF Branch.

(Photo Credit: Sean Parker)