An Opportunity for UK Academia: Reject Critical Social Justice Pseudoscience from the USA

Brief History

It may help to trace the history of this critical social justice movement, and examine how scientific or reliable of a foundation it is to build on. Jumping back to perhaps the beginnings of this branch of thought, the critical theory movement ultimately connects back to Karl Marx’s dialectical philosophy and Sigmund Freud’s individual psychology, but some elements of those have been deemphasized more recently. Critical social justice also has shared roots in postmodernism. Before that, some have argued it links back to German idealism philosophy and GWF Hegel, and that may be stretching it a bit too far (but suffice to say Marx adapted some of Hegel’s way of thinking, such as thinking about groups as having an essence of spirit, as do more recent theorists). Ideas from before the Enlightenment re-emerge in the critical social justice movement too, such as special groups with special knowledge, arguments from authority, illiberalism, limits on speech, but these links become tenuous that far back.

For various reasons, the modern set of critical social justice ideas developed further in American academia in the mid and late twentieth century. This happened primarily in humanities departments. The fashionable scorn in English literature departments for objective standards of evidence and logic, influenced by postmodernism and critical theory, was documented in the 1980s by UC Berkeley English professor Frederick Crews in books such as his 1986 Skeptical Engagements. At that stage in the 1980s, the short step to embracing social justice as an alternative to knowledge had not yet been taken—that has evolved in the decades since then. More recently, the book Cynical Theories (Pluckrose & Lindsay, 2020) and many other sources, have documented how postmodernism has been moulded into the current critical social justice framework. Some schools of education also adopted aspects of these ideas, often inspired by the critical pedagogy work of Paulo Freire. Since then, it appears that many humanities departments in the US have seen the attempted infiltration of critical social justice ideas, and just in the last few years science departments have come under pressure to adopt them too. The absorption into the science departments appears to have faced more resistance, and has been slower than the take up into the humanities.

The Critical Social Justice Formula

The concept of “critical social justice” is a very loose and fuzzy category, yet there is enough cohesion that we are sure the reader will be able to recognize the general pattern of the movement in what follows. In the same way that categorizing tables and chairs is fuzzy, we nevertheless think critical social justice ideas can approximately be identified through a flexible family resemblance method of categorization. The basic structure of the belief system is as follows.

- Oppressor group. This group has agency and power, and essentially is the cause of marginalization and suffering. In some variations of theory, this group is essentially flawed, and/or are guilty by association with historical injustices.

- Oppressed group. Members of this group do not have agency nor power, and are essentially good and/or special.

- Systemic power. The central driving force in modern critical theory, and postmodernism, is power. Power is both an explanatory force in theory, and an assumed major central goal of the oppressor group, for the purposes of oppression. The theory usually includes the design of systems of power by the oppressor group.

- Special knowledge. Some people in the oppressed group have special knowledge that should not be questioned. This is especially true of people with what they call a critical consciousness, which means a revelation-like understanding of the world that they gain from using a critical theory framework.

- Positive change will happen automatically after dismantling. There is a belief that liberation from the power-systems of the oppressor groups will spontaneously bring about positive change. There is usually a lack of a structured set of well-tested ideas that will replace what is dismantled.

- Anti-capitalism. There is almost always an anti-capitalist critique at some point in the narrative.

- Postcolonial theory. European colonization is often equated to the system of knowledge coming out of the Enlightenment, though not in every iteration.

- Language. Language is seen as a powerful cause of the state of society and power. Influenced by postmodernism, modern critical social justice holds the view that changing language can solve societal problems. This sometimes leads to attempts to police language.

- Repressive Tolerance. Herbert Marcuse was a critical theorist who in 1965 made the case for intolerance towards the right wing, and tolerance of left-wing movements. This appears to have come out of an understandable fear of fascism following World War 2, and was written before the horrors of communism were widely known. The idea of repressing the right and liberating the left is still incorporated into some aspects of modern critical social justice.

- Problematizing. The dialectic is a term to be used less today than it once was, and it comes from the ideas of Hegel and Marx, and was continued by the critical theorists of the twentieth century. One interpretation of the dialectic idea is that to make progress, one needs to combine the negative (the critical) with an existing state of the world to get a new improved synthesis (similar to the idea from German idealism philosophy of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis; see also https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-dialectics/). The word critical in critical theory refers to this deeply negative critique—it means using the critical theory formula to problematize a given target. It is different from other approaches to identifying problems in that it is able to problematize anything and everything in society (and we mean everything—including everything the reader holds dear) in a dogmatic and formulaic way.

- Praxis. Written into most critical social justice texts is some call for action. This has been called praxis in earlier incarnations. The action often requires putting people with special knowledge, often from perceived oppressed groups, into power. Such praxis has aimed, for example, to place people into administrative posts in universities, and to embed its central ideas and terminology in policy. Usually, the individuals chosen must believe and perpetuate the critical social justice framework.

- Education. Related to praxis, some critical theorists identified education as a major target for the perpetuation of the belief system (see Paulo Freire, and his intellectual descendants).

- Collectivism. Collectivism, and group identity, is often a running theme in critical social justice. Individualism is generally seen as a problem, and there is a lack of emphasis on individual rights (as opposed to collective group rights).

- Other terminology. Ideas and concepts have continued to evolve in the movement. Terminology has emerged such as positionality (standpoint epistemology), diversity, privilege, intersectionality, equity, belongingness, lived experience, inclusion, and more. Of course, it is the case that some people will earnestly use such terminology, and not believe in the rest of the framework, but at the very least they should know the connections to critical social justice.

Our Additional Observations

- Dogmatism. Critical social justice is different from the standard flexible deductive empirical liberalism that many readers are used to. There is much less nuance and flexibility in the critical social justice mindset. It is more theoretical and based on assumed axioms rather than evidence, and leads to a certainty in its adherents. It does not easily change with evidence.

- Lack of forgiveness. Although this movement can be likened to a religion, it is unsettlingly unforgiving of people who might be seen as an obstacle to the aims of praxis.

- A fearful atmosphere. Most critical social justice applications tend to generate an atmosphere of fear. That in turn can silence people who feel uneasy about the new framework, and that in turn protects the belief system.

This basic formula can be applied with great apparent explanatory power to almost anything, and this is used iteratively with regards to different identified marginalized groups. The historical chronological order in which this has been applied is approximately: class (the original Marxist framework); race; sex; gender; and disability status. This framework has also been used to address climate change. These are all worthy causes, of course, but our concern is that the critical social justice approach may be ineffective and harmful compared to classical liberalism or scientific humanism approaches. Different approaches may yield different results, and indeed may clash vehemently.

The Hope, The Empathy, and the Good

The modern incarnation of critical social justice appears to be sincerely believed by some academics, and seems to flourish in those with great empathy who wish to do good in the world. For some, it is a good cause—a chance to make amends for history and to bring equality finally to the world. It is true, after all, that throughout history there have been oppressor and oppressed groups. There is much appeal in a vision of utopia, of people living together in harmony with nature, where differences between the outcomes of different groups are levelled out. There is a hope of not only equal opportunities, but a hope for equalized outcomes too. There is also hope for a sustainable planet and perhaps a rethinking of the inequalities of capitalism. It is hardly surprising why some believe in it fervently, and why others go along with some of the general gist of the ideas and slogans it produces. It is, in essence, a movement attempting to be empathetic to marginalized communities. It is well-intentioned and laudable for that.

The Problem

Despite being laudable on the surface, we think this vision contains half-truths, and might ultimately be destructive. The essential problem is that it is an unfalsifiable ideology—and by that we mean the negative colloquial connotation of the word to mean a system of unmeasurably vague concepts, with a political and moralistic bent, that departs from hypothetico-deductive empiricism. Like Freudianism, Marxism, Fascism, and religion, we think it is lacking in many elements of a good theory. The critical social justice framework has not passed our scrutiny in terms of the critical thinking tools used by the academic and skeptical community, the same tools the reader may have used to reject astrology, homeopathy, Freudianism, or alien abduction theories. To be specific we have used a scientific toolkit that includes falsifiability, measurability, rationalism, moral philosophy, and so on. We have found critical theory’s modern incarnation to be pseudoscientific. “Pseudoscientific” applies specifically to the part of critical social justice theories that make claims about causes and effects about phenomena in the world—which are essentially scientific claims. Critical social justice appears to be potentially damaging of things we love: such as truth, free speech, free inquiry, good science, stability, cohesiveness, and so on. It could destroy the rationalism and quality of science in university science departments, and it could be destructive beyond that. At the very least, it has the appearance of a new religion that has not yet sufficiently matured to be benign.

We are concerned that the negative aspects of this ideology are being uncritically adopted, and that reasoned opposition is being suppressed in a way that is contrary to the purpose of universities. This is not all a new argument, but we believe there is an optimistic message to be heard. The recent part of the movement originated in the US, whose culture is different to the UK in subtle but important ways. UK universities have a remarkable opportunity to resist adopting the dogmatic framework and the authoritarian aspects of this cultural revolution, and instead apply a rational empirical outlook of which the UK has a proud tradition.

The Role of the University: Truth vs Social Activism

Social activism is a very important part of society, but it must remain separate from universities. This is an argument that has also been made by the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. The universities’ ultimate goal must be truth, and not social activism. Universities act as a reality check on social activism and help distinguish between good ideas and bad ideas. Individual academics have the freedom to be activists, but activism must not be embedded into university mandatory policy or speech codes. Every generation produces some good ideas that should be incorporated into culture, and a tremendous number of bad ideas that should be rejected. Universities should be independent from all this so that academics—ideally some of the brightest in society—are free to criticise these new ideas. Without a sector of society dedicated to critiquing new ideas without threat of reprisal, what disasters, iatrogenic treatments, or social contagions, could spread in countries? In the twentieth century, Lysenkoism caused agricultural disaster in the Soviet Union, precisely because Marxist ideology was incorporated into education. We do not know what will be the result of incorporating the critical social justice ideology into UK universities, nor how many years it would take. Our argument is that it is probably prudent to not install any ideology into the universities, whether it be religion or critical social justice.

A New Religion

The new critical social justice movement has many elements of a new religion, and education should be kept separate from religion. Of course, we must tolerate those that subscribe to the new rituals of this religion, whether that be declaring pronouns where none are needed, or public prayer-like declarations of adherence to critical social justice ideals. Religious ideas are of no concern so long as they kept separate from university curricula, and in fact religious people bring valuable ideas to universities. As equally as we oppose the encroachment by the religious right to thwart the teaching of evolutionary theory in the southern states of America, we equally oppose encroachments on our curricula that any new religion attempts to impose. Without such encroachment of religion into academia, we will be able to appreciate, and like, and tolerate, those coming from different religious perspectives. Keeping critical social justice terminology out of university policy would likely create a better and less fearful atmosphere.

New religions generally are most dangerous in two periods of their development: the early years, and in periods in which they have gained political power. The former can be demonstrated by the many strange new cults that sprang up in the twentieth century, from Scientology, to Jonestown, The People’s Temple, and Heaven’s Gate. There is some irony that these new religions turned out to be more dangerous than the established religions they replaced. The second dangerous period is when religions gain political power. The danger of authoritarianism is well demonstrated by the theocracies of the middle ages in Christianity, and in more recent examples of when religions gain power over policy. The wise solution is to be vigilant and to realize that new religions might have problems of cultism, and should therefore not be embedded into policy, law, media, and the universities. This equally applies to the new religion of critical social justice. Just as that most religious people are good for the most part, the same is true of people who have adopted critical social justice as their moral guide. We should all be tolerant of other religions. But our respect quickly fades when they try to impose their ideas on our beloved universities and science departments, and embed what is essentially religion, into university policy. Individuals should have full freedom to believe the critical social justice framework, and to work in universities as administrators or professors, and to be activists outside of the university. Academics should not, though, bring any religion, whether it be Anglicanism or critical social justice, into the written rules and guidelines of secular state universities.

Of course, people who subscribe to some of the ideas of critical social justice may be at different levels of knowledge and adherence within the framework. As in religion, there will be those who know the framework inside out and are active to promote it (like priests, perhaps). Others will know the terminology quite deeply and attempt to spread the word quite vigorously (the faithful). Others will not understand the whole framework, but will agree with the nice-sounding terminology and pass it on to others (the empathetic uninformed). Others may feel it is wrong, but may be told their feeling may be a sign of an internal problem in them—a moral flaw. Others may feel some fear of the critical social justice mob, and conform. In this way, millions of people may not agree with critical social justice dogma, but be too scared to say something.

The Choice and the Opportunity for UK Universities

We do not have to import everything the US creates. Yes, the US has produced so much of the world’s reliable science and knowledge, but that does not mean we have to believe everything US academia puts out. There is an opportunity here for the UK to resist this new ideology and choose instead the tried and tested ideas of empiricism, humanism, and classical liberalism. This approach has been at the heart of British universities for many years, and has underpinned much of the economic, moral, and technological development derived from them. Developing from the wonderful but fallible ideas of John Locke, and later John Stuart Mill, classical liberalism proposed that we treat each other first and foremost as individuals, not as members of an interest group. Classical liberalism was very much affected by the grounded and empirical bent of British philosophy, which contrasts quite sharply with German idealism (e.g., Hegel, Marx, the Frankfurt School’s critical theory, etc), and French postmodernism (e.g., Foucault, Lacan, etc). This is not to underestimate the wonderful empirical science that was and is done in those countries. With US academia infected with ideas from the postmodernists and a diaspora of critical theories, UK academia has a marvellous opportunity to accept the scientific discoveries from over the Atlantic, and reject the pseudoscientific nonsense coming from ideologically captured humanities departments in the US.

To be fair, the state of American universities is actually more nuanced than the impression we give here. Within American universities, there is an important debate taking place around the distinction between equity (of outcomes) and equality (of opportunities). It remains to be seen which model will prevail. The populace of the US more generally appears to still favour the ideal of meritocratic advancement. Although most US universities have succumbed for now to some critical social justice ideology, no one can say where things will stand ten years from now. So a critic might justifiably object to us equating critical social justice ideology with the US.

We live and work here, so this is why we are focused on the UK here. We have to have hope that British universities do not catch America’s ideological cold, and there is some reason to be hopeful: the past has shown the UK has been resistant to German idealism philosophy and related ideologies.

In every British university department right now, there are wonderfully oppositional and grounded types among the student population and academics. We do not mean this in a jingoistic way—these oppositional thinkers are both British and international. These academics and students are seeped in the traditions of empiricism and can smell nonsense, and some of them dare say something, some are biding their time, while others want a quieter and more comfortable life.

There are also promising signs in the new formation of many branches of Academics For Academic Freedom in UK universities.

The universities of this small nation have produced some of the sharpest critical thinkers and social critics. We could name quite a few, but will allow the reader to think for themselves on this matter. We are encouraged by a new breed of critical thinkers in the UK in the Millennial generation, and the many common-sense students we see in Generation Z, and the straightforwardness we see in our Generation-Alpha children. Every generation in the UK will continue to produce outspoken intellectual rebels like those who have come before. It is for this reason that we are optimistic that UK universities can gain ground over American universities, if we are brave enough to choose it.

The opportunity for UK universities is this: we can observe how racial and gender tensions have worsened in some US universities via regressive aspects of critical social justice overtaking their administrations. UK universities could fill the tremendous demand for non-indoctrinating education that most students, parents, and employers want. The majority of parents do not want their child to return from university disliking their country, their skin colour, gender, or their other immutable characteristics. Those UK universities that choose to eliminate indoctrination should see increases in their enrolment. There is a great demand and hunger for good, serious, non-religious education that gives students all the facts and testable theories they need to help society meet the challenges ahead. Not only that, if the UK gains the reputation as having non-captured universities, we may see influxes of international and American students wishing to escape the indoctrination hot-houses they have at home. To do this will take courage from a sizable number of academics— courage to speak up politely and constructively, and perhaps impolitely at times. The message should be: we do not subscribe to your religion, and we do not want it institutionalised into the universities.

Acknowledgements

We thank Frederick Crews, Richard McNally, Amy Salkeld, and Abhishek Saha for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. We also acknowledge the many authors who have influenced this article but we have neglected to name: this article is very much a critical assessment by two science academics of a wider discussion with very creative ideas (often too creative) coming from many thinkers. Our contribution here, we hope, is that we critically exclude some of the more creatively risky ideas (e.g., conspiracy theories, assuming intent, and so on), and present the wheat minus the chaff. The ideas presented in this essay are where we are in 2023 after observing the world as scientific skeptics for more than a decade. In a decade’s time we will likely modify our take on this social phenomena.

(Photo Credit: In the public domain)

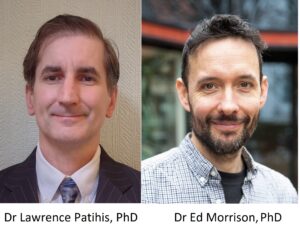

About the Authors

Dr Lawrence Patihis, PhD is a British/American psychologist interested in distinguishing science and pseudoscience, with a particular interest in applying this to claims of both repression and oppression as invisible entities and explanatory forces. He was formerly a true believer in repression and oppression as explanatory forces, and has written many peer articles on the former, and spent years evaluating the latter.

Dr Ed Morrison, PhD is a psychologist interested in evolutionary psychology and sex differences in behaviour and strategies in humans and animals. He is also interested in theories of beauty. His interest in the present topic somewhat derives from the some of the controversies in trying to suppress discourse in some of his areas of interest.